The Hudson Valley has become a mecca for commercial art spaces, and an unlikely one at that. It’s also where long-time art advocates Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu call home, and recently opened their 20,000-square-foot private exhibition, Magazzino. Focusing exclusively on postwar and contemporary Italian art, the husband-and-wife duo alongside architect Miguel Quismondo and Magazzino Director Vittorio Calabrese, hope to pay tribute to the Arte Povera movement and bring an understanding to those in the U.S.

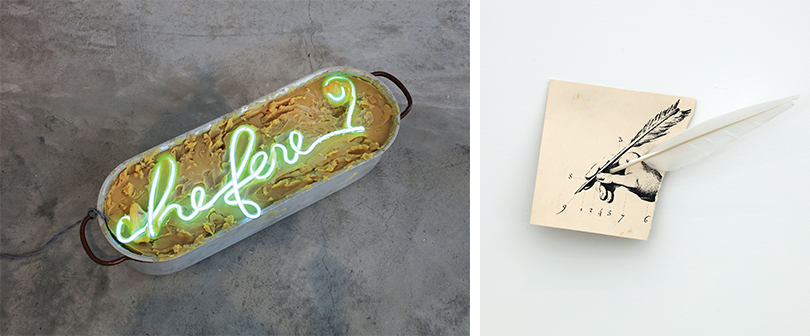

What began in 1967 was a revolution that translates literally to “poor art.” The term was coined by an Italian art critic, Germano Celant, who organized his first Arte Povera-style show that year. At the time, “poor” didn’t mean impoverished but referenced a type of minimalism that  Polish director, Jerzy Grotowski, incorporated into his theater production. Grotowski wanted to bypass all barriers that distracted from the connection between the actor and the audience. Work from the Arte Povera movement emulates that same connection. Calabrese explained, “It is art that goes straight to the core. The way Arte Povera does that is it speaks directly to the world. It uses everyday materials as common language.”

Polish director, Jerzy Grotowski, incorporated into his theater production. Grotowski wanted to bypass all barriers that distracted from the connection between the actor and the audience. Work from the Arte Povera movement emulates that same connection. Calabrese explained, “It is art that goes straight to the core. The way Arte Povera does that is it speaks directly to the world. It uses everyday materials as common language.”

Margherita Stein of Galleria Christian Stein, founded in 1966, was a pioneer of Arte Povera before the movement was even rightfully defined by Celant. Stein took on her husband’s name in order to find respect throughout the art world and became one of the leading gallerists of her generation. Throughout her career, Stein went on to bring Italian concepts like Arte Povera and Spatialism to the U.S., as well as extend her support to young, aspiring artists along the way. Today, Stein serves as the inspiration behind both Magazzino and its inaugural exhibit, Margherita Stein: Rebel With a Cause.

The former dairy distribution center-turned-computer factory has kept its same industrial feel, but doubled its square footage. Magazzino—which means “warehouse” in Italian—was designed to juxtapose the old and the contemporary. “We saw the building was in disarray and we knew it needed a full gut renovation,” Quismondo explained, recalling the two-year process. “We wanted to create a dialogue between what existed there before and what is new.”

Both Quismondo and the owners agreed to keep the original bones of the building but transformed its signature L shape into a rectangle. The new addition and wall-to-wall glass allows for an abundance of light as well as planety of exhibition space to be explored. Magazzino also features a 5,000-volume library to serve as a place of study and conversation and at the center, a courtyard with a reflecting pool.

During the design, it was important for Quismondo to keep the same structure and make sure the natural materials remained intact. He ended up exposing many of the building’s original metal beams and keeping its concrete flooring—both which hark back to the principals of the Arte Povera era. Its stark, fortress-esq exterior while foreboding, Quismondo mentioned is intentional. “The architecture should take a step back and allow the art to speak by itself. We’re trying to disappear a little bit.”

The current artwork on display at Magazzino—almost all of which has never been shown in the U.S.—is a combination of works that were once owned or had been exhibited by Stein at some point. The collection spans over four decades, highlighting past Arte Povera patrons along with the next and newest generation that Olnick, Spanu and Calabrese selected. “The last room of Magazzino is dedicated to younger artists,” said Calabrese. “They’re part of the show not because they’re involved in Arte Povera, but because they represent Margherita. They never got to meet her but she’s their mentor—they felt close to her mission in bringing Italian art to the U.S.”

The current artwork on display at Magazzino—almost all of which has never been shown in the U.S.—is a combination of works that were once owned or had been exhibited by Stein at some point. The collection spans over four decades, highlighting past Arte Povera patrons along with the next and newest generation that Olnick, Spanu and Calabrese selected. “The last room of Magazzino is dedicated to younger artists,” said Calabrese. “They’re part of the show not because they’re involved in Arte Povera, but because they represent Margherita. They never got to meet her but she’s their mentor—they felt close to her mission in bringing Italian art to the U.S.”

Aside from exhibitions, Magazzino aspires to also act as a medium for Italian art education. Over the next year, the space will welcome screenings, lectures and performances that in turn, will help continue to expand the conversation to audiences outside of Europe.

A large part of why Olnick, Spanu and Calabrese started this project in the first place was because they, like Stein, felt that Italian art was underrepresented in America. And although Magazzino’s debut exhibition is rooted in the past, Calabrese hopes that their initial tribute to Arte Povera and Margherita Stein lays the groundwork for future, more contemporary programs.

MORE Lifestyle STORIES

Get an inside vue on the latest in luxury. You heard it here first.